Across Europe, shadow markets constitute a significant portion of the economy. According to some estimates (Schneider, 2019), an average of 16 percent of GDP in EU member states is generated by the shadow economy. In Eastern and Southern Europe, the share of GDP produced by the shadow economy is even higher. On the one hand, governments admit that activities carried out within shadow markets create added value– they are included in official estimates of GDP among EU member states. On the other hand, governments have attempted to combat the shadow economy by introducing all kinds of policy measures aimed at reducing its operations as far as possible. This aim of eradicating the shadow economy at all costs is often counterproductive; it leads to punitive measures and less productive economic activity. As demonstrated by the great extent of shadow economies in some European countries, these efforts by governments are not always successful. In this report, we argue that one of the reasons why governments are often unsuccessful in reducing the extent of the shadow economy is that the policy measures are not directed towards those causes that drive the shadow economy. It is important to know not only how much activity takes place in the shadow economy, but also why people choose to engage in such activities. The successful reduction of the shadow economy is only possible once we know what drives it.

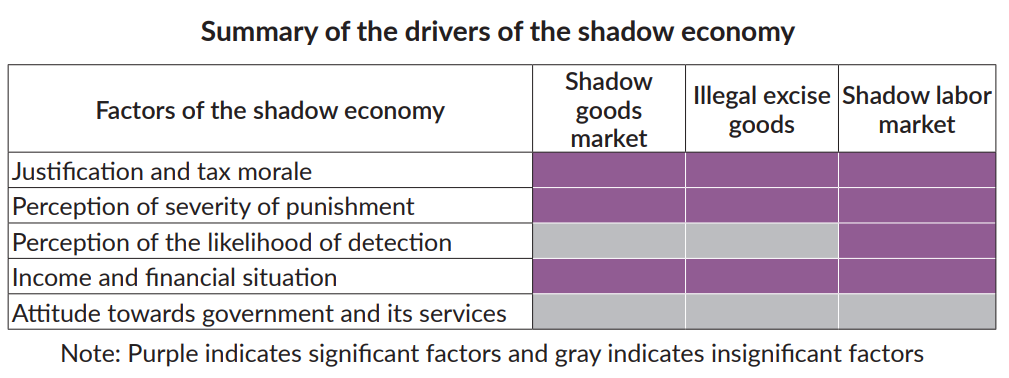

A new research report Reducing Shadow Economies. From Drivers to Policies from the Lithuanian Free Market Institute, which analyses the shadow economies in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Sweden and the Czech Republic, provides new evidence on taxes and regulations as the primary causes of the shadow economies as well as other significant factors that come at play and affect the extent to which taxes and regulations determine the prevalence of undeclared or illicit activities. The research suggests that robust tendencies exist in relation to these factors. The income level, justification of the shadow economy and the perceived severity of punishment are among the robustly significant drivers across all of the countries analysed. The perceived likelihood of being detected is only significant for the undeclared labor market.

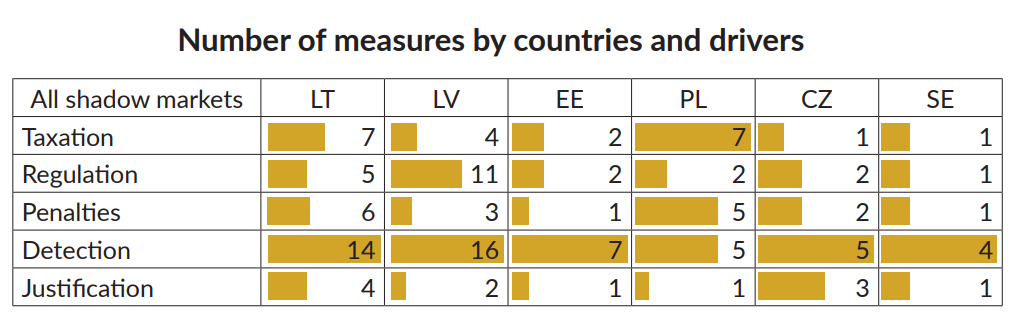

The research also shows that in their fight against the shadow economies the governments tend to focus on policies that increase detection as well as on taxation and regulatory measures. Out of a total of 126 measures across the six countries, 51 (or 40 percent of all measures) focus on detection, 23 (18 percent) on regulation and 22 (17 percent) on taxation. Importantly though, most of the tax and regulatory measures (71 percent) are designed at a stricter enforcement of tax rules and more restrictions on economic activity rather than at reducing the tax and regulatory burden. Only 13 measures out of 126, or a mere 10 percent, were directed towards some kind of easing of the burden and costs of taxes and regulations.

Our study suggests that the accuracy of policy measures is 57 percent, which means that only slightly more than one-half of policies address those drivers that are significant.

So the policy strategies against the shadow economy are skewed towards increasing the costs of participating in the shadow economy rather than rethinking the costs of legality and making legal operations more attractive. Those responsible for these strategies often ignore its intrinsic causes. In order to effectively counteract the shadow economy, it should not simply be viewed as a source of criminal offences. Instead, it is important to recognize that the shadow economy is primarily concerned with the creation of value. This means that the fight against the shadow economy is at its most productive not when illegitimate activities are completely eradicated, but when they are transitioned from the unofficial to the official domain. In order for this to occur, one needs to consider the legal environment in which such economic activities are carried out. Is this environment conducive to working and doing business? Incentives to participate in the shadow economy always stem from restrictions placed upon legal economic activities, be they taxes or regulations. The important way to curb the shadow economy, therefore, is not only to increase the burden on illegal activities but to render legal operation more attractive by creating clear and reasonable rules and reducing the applicable costs of taxation and regulations.

The report offers country profiles with a comprehensive overview and evaluation of the policies measures designed to reduce the shadow economies in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Sweden and the Czech Republic.

About the research

In our research we employed a direct (micro), survey-based approach to investigating the shadow economy and regression analysis of the individual data from the surveys to identify its significant drivers. These surveys surveys into public perceptions of and engagement in the shadow economy were conducted in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Poland, Sweden and the Czech Republic during March and April 2018. The Lithuanian Free Market Institute conducted the first study in this series, Shadow Economy: Understanding Drivers, Reducing Incentives, in 2015. The volume of data gathered and the geographical span of the survey, covering six countries, provided a unique opportunity to undertake a quantitative analysis of what drives the shadow economy.

The research was conducted by the Lithuanian Free Market Institute in cooperation with Prof. Dr Friedrich Schneider of Johannes Kepler University Linz, Dr Arnis Sauka (Latvia), Caspian Rehbinder (Sweden), the Estonian Business School, the Civil Development Forum (FOR, Forum Obywatelskiego Rozwoju, Poland), and the Centre for Economic and Market Analyses (CETA, Centrum ekonomických a tržních analýz, Czech Republic).

The research was supported by PMI Impact, a grant award initiative of Philip Morris International (PMI). The views and opinions expressed in this article and the research report are those of the Lithuanian Free Market Institute (LFMI) and do not necessarily reflect the views of PMI. In the performance of its research, LFMI maintained full independence from PMI. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in this report lies entirely with LFMI.

The research “Reducing Shadow Economies From Drivers To Policies” can be found here.

Galleries from report launch events in Vilnius and Brussels can be found here.