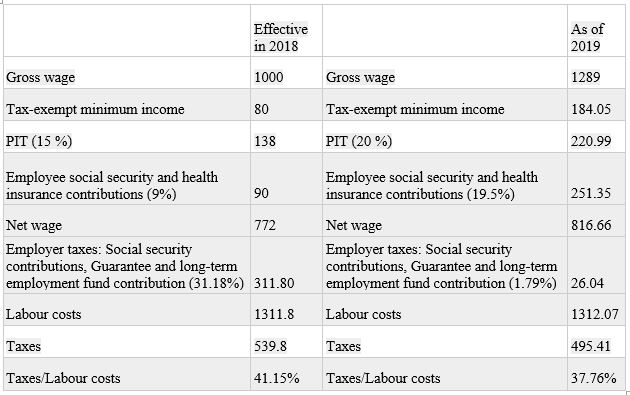

In late June the Lithuanian Parliament adopted a law that consolidated the employer and employee base for social security contributions and significantly cut the rate of contributions. Labor taxes were consolidated on the employee’s side, but the gross salary (salary before tax) will be recalculated by increasing it 1.289 fold. The employer’s rate of social security contributions was cut from 31.18 to 1.47 percent, and the employee’s contributions rate was raised from 9 percent to 19.5 percent.

The idea of consolidating social security contributions was first put forward by the Lithuanian Free Market Institute in 2014. Two years later four major political parties adopted this idea in their election programs and eventually it was incorporated in the new administration’s work program. Importantly, the consolidation of social security contributions is a step forward in terms of taxpayers’ awareness raising and creates a platform to advocate for further reductions in social security contributions. Notably, this reform will also lift Lithuania’s Doing Business ranking in the category of Ease of Paying Taxes from the 18th to the 6th position and the country’s overall ranking from 16th to 13th.

Lithuania has also introduced a cap on social security contributions for income exceeding a sum of 120 average wages per year (which is 8,900 euros per month) and provided for a gradual reduction in the “capped” level of employment income (to 6.200 Eur in 2020 and 4.400 Eur in 2021). The cap on the application of the tax deductible income has been increased from 1.3 to 2 average wages (1760 Eur). Mandatory health care insurance payments will not be capped.

These amendments will help to ease Lithuania’s labour tax burden which presently is heavier than the OECD member states’ average (40 percent vs. 36 percent). It will benefit 1.3 mln working population in Lithuania. An economic survey released by OECD on the occasion of Lithuania’s accession to this organization states that, in order to secure inclusive growth, Lithuania must reduce social security contributions, especially for low-income workers, while ensuring that benefits and deficit targets are maintained.

Although a cap on social security contributions is a step towards a fairer tax system, the “capped level“ is still very high. By comparison, the neighbouring Poland caps social security contributions at 2.3 average wages. Even the Scandinavian welfare state of Sweden caps pension contributions at 1.2 average wage. Even after 2021 Lithuania will still have one of the highest levels of a social security contribution cap in the EU.

At the same time though, Lithuania has phased out its 24 year-old flat tax regime. The personal income tax has been raised from 15 to 20 percent (with the basic pension fund being transferred from the state social insurance fund to the state budget) and introduced income tax progressivity. A tax of 27 percent has been imposed on income exceeding 120 average wages per year, with this income level to be lowered in the years to come to the size of the income capped by social security contributions.

The progressive income tax will have a minor impact on the state budget. The expected revenue is estimated to amount to around 4 mln Eur in 2019. The progressive PIT will be the second smallest source of budget revenues and its introduction can be viewed as a meaningless step.

Those reforms are estimated to bring budget losses of 200 mln Eur in 2019, but the government is planning to offset those losses through anti-shadow economy initiatives and economic growth. According to EC and Bank of Lithuania, economic growth is forecast to remain strong but is expected to slow down from 3.1 % in 2018 somewhat to 2.7% in 2019.

Labour taxation in Lithuania:

Along with the tax reform Lithuania adopted a very unsustainable pension reform. Working people will no longer be able to transfer 2 percent of their mandatory social security contributions into the second-pillar pension funds (the previous law stipulated a gradual increase in this proportion). Instead, a new formula for pension accumulation has been adopted, 0%+4%+2%. Contributions into pension funds will now comprise 4 percent of personal income and a supplementary contribution of 2 percent of the national average salary paid for the participant out of the state budget. Basically this means that the goal of transforming the PAYG system into saving for retirement is being abandoned. The law also foresees a quasi-mandatory mechanism of involvement in second-pillar pension funds. Given a reduction in the working-age population, the adopted pension reform is a serious step backwards.

Another distressing amendment is that the State Social Insurance Fund Board will become the only payer of pension annuities. This means that contributions accumulated in private pension accounts will ultimately end up in a state annuity fund. There will be fewer options for deferred annuity and inheritance of unpaid part of annuity.

These policy reforms were discussed at a policy conference “Can we do more to boost Lithuania’s competitiveness” which the Lithuanian Free Market Institute co-hosted with the Ministry of Economy of Lithuania and the Heritage Foundation in Vilnius on July 9th. The conference featured Simeon Djankov, Director of the Office of the Chief Economist of the World Bank and co-author of Doing Business Index, Ambassador Terry Miller, Director of the Center for International Trade and Economics at The Heritage Foundation, and Anthony Kim, Research Manager and Editor of the Index of Economic Freedom of The Heritage Foundation.